Access to care and treatment for mental health issues remains out of reach for most of the population in the United States even though more than one-fifth of U.S. adults (21%, 52.9 million) had a mental illness1 in 2020.2 Even among individuals with insurance, issues such as a lack of available providers, inadequate insurance coverage, high out-of-pocket costs, and fragmented care persist. This brief defines the barriers to accessing mental health care in the United States and highlights the key focus areas policymakers should prioritize to improve access, coverage, and affordability of care.

This Isn’t New … and It’s Getting Worse

From 2008 to 2019, the number of adults aged 18 or older with any mental illness increased from 39.8 million to 51.5 million, a nearly 30% increase.3 The pandemic has further exacerbated mental health problems for all ages; among adults aged 18 or older who had serious thoughts of suicide in 2020, more than one-fifth (21%) listed COVID-19 as the reason for those thoughts.2 While progress has been made to reduce the stigma around mental health issues, the problem persists and prevents many people from accessing care. 4

The United States is also facing a growing youth mental health crisis. From 2009 to 2019, the share of high school students who reported experiencing persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness increased 41%. 5 From 2010 to 2020, suicide death rates increased by 62% among adolescents aged 12 to 17.6 In early 2021, emergency department visits for suicide attempts were 51% higher for adolescent girls and 4% higher for adolescent boys than in early 2019.7 Furthermore, in October 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association declared child and adolescent mental health a national emergency.8

Mental Health Professional Shortages

The United States needs more mental health professionals. As of Sept. 30, 2021, an estimated 129.6 million people lived in one of the 5,930 federally designated mental health care Health Professional Shortage Areas. Less than one-third of the U.S. population (28%) lives in an area where there are enough psychiatrists and other mental health professionals available to meet the needs of the population — in fact, most states have fewer than 40% of the mental health professionals needed. The percentage of need met ranges from as low as 5% in the District of Columbia to 69% in New Jersey (Figure 1).9 Additionally, more than half (51%) of counties in the United States have no practicing psychiatrists.10

The shortage and maldistribution of mental health professionals across the country further impedes access to mental health care. Rural areas, where 14% of the U.S. population (or 46 million people)11 live, have disproportionately low numbers of practicing mental health professionals compared with urban areas. Among nonmetropolitan counties, 65% had no practicing psychiatrist as compared with 27% of metropolitan counties.8

While the number of aspiring psychiatrists matched to a medical residency program has grown over the past five years,12 educating and training physicians takes over a decade. Psychologists, social workers, licensed therapists, and other mental health professionals who can be trained more quickly than psychiatrists play a critical role in expanding access to mental health care.

Navigating a Maze

Even when mental health providers are geographically accessible to patients, insured patients often find it difficult to find a provider who is in their insurance network and end up paying high out-of-pocket costs for out-of-network care; in some cases, they do not seek care at all.

In 2020, among adults aged 18 or older who had any mental illness in the past year and a perceived unmet need for services, 30% reported not receiving care because their health3 insurance did not cover any mental health services or did not pay enough for mental health services. This number was similar for those with serious mental illnesses.2

While the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 mandates equal coverage and benefits for mental health and general medical conditions, gaps between insurance coverage for mental health conditions and other medical conditions still exist and are growing.13 The insurance practices that are most likely to impede access to mental health care — including arbitrary medical necessity standards, network inadequacy, and fail-first approaches — remain pervasive among insurance companies.14

For the 27.4 million15 nonelderly individuals without insurance, accessing and affording mental health care is even more difficult, particularly in states that have not expanded their Medicaid programs. In 2019, adults aged 18 or older who had any mental illness in the past year were significantly more likely than those without any mental illness to be uninsured (10.8% versus 9.6%, respectively).16 Uninsured adults with depression or anxiety were also more likely to not receive any treatment compared with their insured counterparts.17

Who Is Really in My Insurance Network?

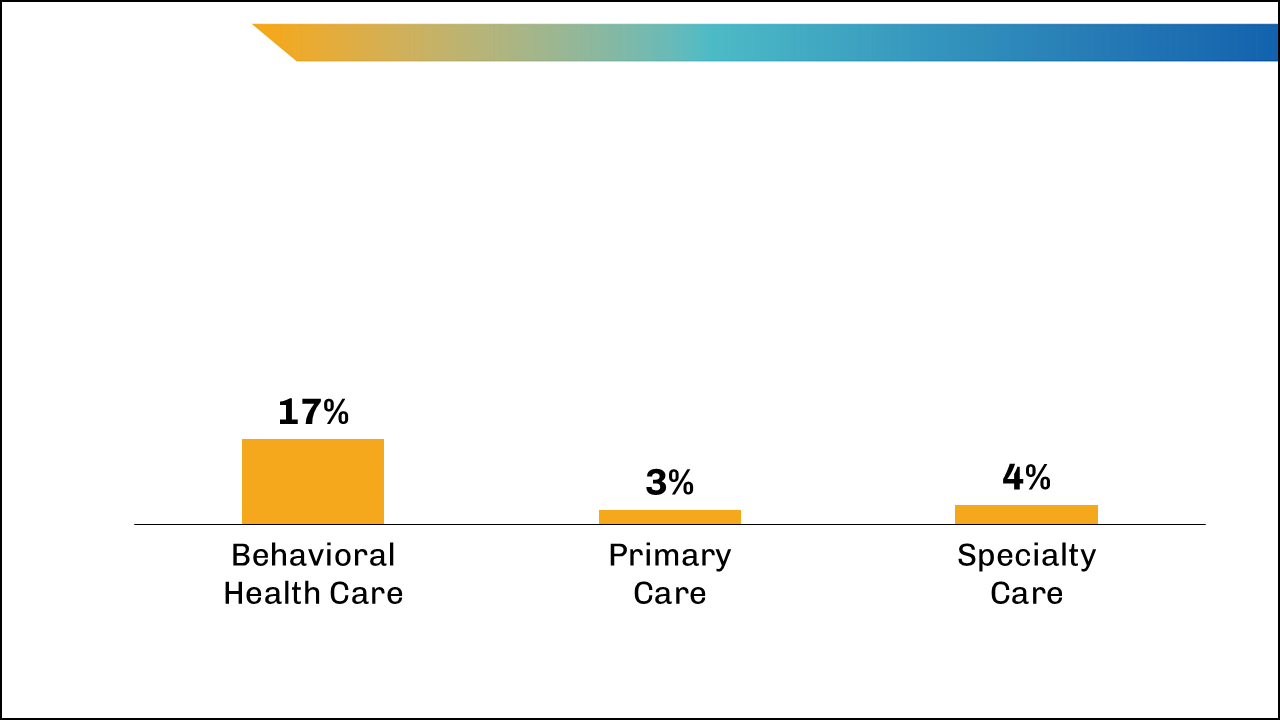

In a survey conducted by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) in 2015, 1 in 4 respondents did not have a mental health therapist in their health plan’s network as compared with 1 in 10 who did not have a medical specialist in their health plan’s network.18 Additionally, patients often find themselves wading through “ghost” or “phantom” networks — a directory of providers who supposedly take the patient’s insurance but who often do not take new patients, do not exist altogether, or are not “in network” with the insurance plan. A recent study found that in Oregon’s Medicaid managed care organizations, 67% of mental health prescribers and 59% of mental health nonprescribers were “phantom” providers who did not see Medicaid patients.19 Due to these barriers, the patients who can afford to do so are much more likely to go out-of network for mental health services. A report analyzing claims data for commercial PPO plans covering 37 million individuals found that, in 2017, 17% of behavioral health office visits were to out-of-network providers as compared with 3% of office visits to primary care providers and 4% of office visits to medical/surgical specialists (Figure 2).20 These differences were even greater in states like Alaska, where 64% of behavioral health office visits were out-of-network compared with 22% of primary care visits; New Jersey (41% versus 4%, respectively); and South Carolina (20% versus 4%, respectively).15

Patients who turn to their primary care providers (PCPs) for mental health services face a different set of barriers. In the 1980s, many insurers began “carving out” mental health benefits, meaning they outsource mental health services to different vendors that have their own unique network of doctors. However, patients and their PCPs are often unaware of this because insurance companies do not make this information widely available. As a result, PCPs do not get paid for rendering mental health services since they are often out-of-network with the vendor, and the cost ultimately gets passed on to the patient.21 A study by KFF found that as of July 2021, 7 of the 41 states that contract with Medicaid managed care organizations always carved out specialty outpatient mental health services from their contracts.22 Carve-outs (and the limited information on them), among other barriers, impede true parity of access to mental health care.23

No Insurance Accepted

In addition to insurance network inadequacy, another pressing issue that is limiting access to mental health care is the large proportion of psychiatrists who do not accept insurance. A 2014 study found that only 55% of psychiatrists accepted private insurance as compared with 89% of physicians in other specialties in 2009-2010. The disparity was similar for Medicare and Medicaid.24

Low reimbursement rates are the main driver of this disparity. For similar mental health services, nonpsychiatric medical doctors received anywhere from 13% to 20% higher in-network reimbursement than psychiatrists. On the other hand, for services provided out-of-network, the 5 median reimbursement was 6% to 28% higher for psychiatrists than for nonpsychiatric doctors.25 These low reimbursements disincentivize mental health professionals from joining insurance networks.26

Among mental health professionals who do accept insurance, reimbursement rates vary based on the insurance type. Providers are less likely to accept Medicaid or Medicare because their reimbursement rates are lower than private insurance. Despite being the largest payer for mental health care,27 Medicaid generally reimburses providers at lower rates than both private insurance and Medicare, making access particularly difficult for patients with Medicaid coverage. A 2017 study found that only 46% of psychiatrists were willing to accept new patients covered by Medicaid; 75% were willing to accept new patients covered by Medicare and 69% were willing to accept new patients covered by private coverage.28

First, Let’s … Fail?

The criteria for how insurance companies define the “medical necessity” of mental health services are inconsistent, which results in high rates of claim denials. In a 2015 survey conducted by NAMI, 29% of respondents reported that they or their family member had been denied mental health care because their insurance company had deemed the care medically unnecessary; conversely, only 14% of respondents were denied general medical care for the same reason.29 In 2020, one-fifth of the approximately 765,000 medically necessary claims for behavioral health services were denied.30

Insurance companies usually adopt these restrictive practices, which also include paying mental health providers lower rates than other medical providers and excluding mental health providers from insurance networks, in an attempt to lower costs by increasing barriers to care.

Insurance companies may also reduce patient access to mental health services in ways that do not clearly violate parity standards. Insurance companies often employ a “fail-first” strategy for mental health services, meaning that they will cover a more expensive treatment only after a patient shows no improvement through a cheaper treatment. Such strategies impede timely access to care and worsen outcomes. As a result, care is often guaranteed only when patients are in crisis, and even then, care depends on providers and other resources being available to them.

What Can Be Done?

Integrating and Coordinating Care

One-third of adults aged 18 or older who reported having a mental illness and an unmet need for services indicated that they did not receive care because they did not know where to go for services.2

Historically, diagnosis and treatment of mental health illnesses have been separated from physical illnesses. Different health care providers work in their own silos, and collaboration to coordinate a patient’s care is not standard practice. This is driven by a combination of factors including a lack of integrated technology and training, regulations and laws, and misaligned payment incentives.

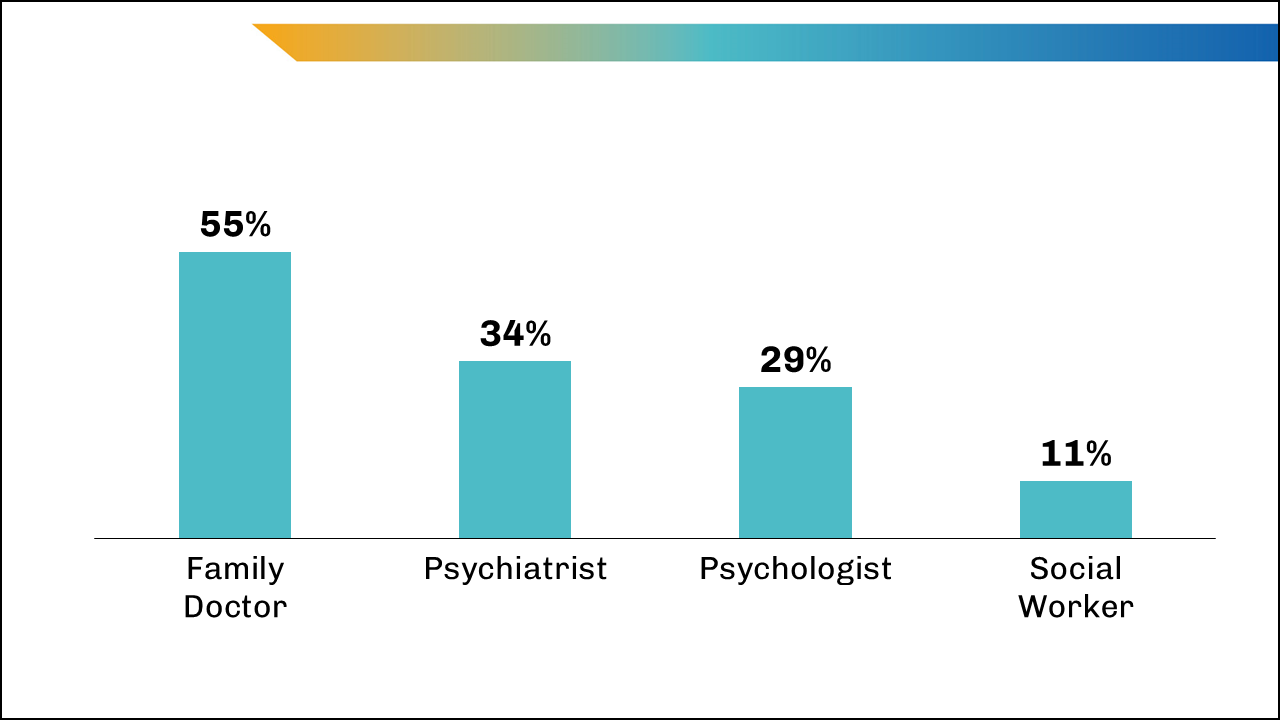

PCPs often serve as the entry point into the care system for patients. As a result, patients with mental health illnesses are more likely to discuss them with a primary care doctor than with psychiatrists or other health professionals (Figure 3). Additionally, over one-third of the care and one-quarter of the medication prescribing for patients with serious mental illnesses was done by PCPs.31 Primary care settings play an important role in providing mental health services and treatment, but PCPs often lack time, training, and resources to do so effectively on their own.

One issue is the lack of electronic health record (EHR) usage among mental health providers in nonprimary care settings. A 2012 report found that only 20% of behavioral health practices had adopted EHRs while 60% of other health care providers had done so.32 A 2016 study found that for 27% of patients with depression and 28% with bipolar disorder, their primary care records showed no indication of their mental illness.33 Missing information about previous diagnoses and treatment can harm patients. An incomplete picture of the patient’s health can lead to medication errors, under- or over-diagnosing, and mismanagement of comorbid conditions.

While primary care settings may be the most accessible entry point to mental health care for many patients, PCPs are already stretched thin and many are unable to provide patients with even routine preventive and chronic care.34 Moreover, fewer and fewer Americans have a primary care provider.35

Given how frequently individuals bring up mental health concerns in primary care settings, and the fact that PCPs may not have the time or training to treat mental health issues, integrated systems that help PCPs coordinate care and connect patients with the right mental health provider can significantly improve access and outcomes. Many different types of integrated care models have emerged in recent years. Yet, implementation has lagged mainly due to fragmented reimbursement systems, regulatory barriers, and lack of interoperability.

Individuals with mental health issues tend to have a higher rate of physical comorbidities.36 There is no doubt about the connection between the mind and body, and evidence suggests that for many commonly occurring chronic physical illnesses, treatment of comorbid mental health issues leads to improvement in both mental and physical health.37 This is where integrated behavioral health, or “collaborative care,” comes into play.38 Integrating and coordinating care across medical and behavioral health providers is crucial to delivering wholeperson care and is a first step toward taking a preventive approach to mental health care. Building models where trained psychologists or social workers practice within a primary care setting can bridge the divide between mental and physical health.

Investing in Technology

Telehealth has played a significant role in improving access to mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, less than 1% of mental health and substance use care was accessed through telehealth, compared with 40% from March through August 2020. While telehealth use for other medical services has dropped by more than 50% since the return of inperson care, telehealth use for mental health and substance use services has remained fairly consistent, accounting for 36% of visits from March through August 2021.39

Telehealth continues to play an important role in the ongoing pandemic and can be a promising near-term solution to expanding access to mental health care, especially in rural areas. Between March and August 2021, the proportion of patients in rural areas who used telehealth for mental health and substance use services was 55%, compared with 35% in urban areas.39 However, preserving this heightened access to care and expanding these efforts largely relies on extending the policy and payment flexibilities implemented under the COVID-19 public health emergency.40 In July 2022, the U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation that would help extend some of these telehealth policies for Medicare through 2024.41 However, it remains to be seen whether it will be passed into law and whether these extensions will prompt lawmakers to consider permanent telehealth reform.

Enforce, Expand, Insure, and Enact

The United States does not currently have the capacity to provide the necessary mental health care to millions of people — nor is accessing such care easy for most patients. There are short- and long-term opportunities to create policies that prioritize growing the workforce, expanding insurance coverage for patients, increasing reimbursement rates for providers, and enforcing state and national parity laws.

In March 2022, the Biden administration proposed a $700 million investment to expand the mental health workforce in rural and other underserved areas.42 While Biden’s proposal showed that policymakers are increasingly recognizing the problem of workforce shortages in mental and behavioral health, Congress has yet to allocate any such funding as of September 2022. Funding is crucial to solving these workforce shortages, and Congress needs to invest in programs to recruit and train more mental health professionals.8

Expanding the workforce is necessary but it cannot alone ensure patients can access care in the near term. If existing mental health professionals continue to be excluded from insurance networks, patients will continue facing barriers to accessing care.43

Furthermore, the low reimbursement rates for mental health professionals further disincentivize them from accepting insurance. Policymakers should consider implementing policies that ensure mental health professionals can join insurance networks and increase reimbursement rates for these professionals. In addition, insurers and policymakers need to make greater efforts to ensure all patients seeking care have reliable insurance, including coverage for mental and behavioral health services.

Medicaid is the largest payer for mental and behavioral health services in the country,27 but because 12 states have not expanded their Medicaid programs as of Sept. 20, 2022, 44 many individuals (2.2 million as of 2019) fall into the coverage gap45 — meaning they are uninsured because they do not meet the eligibility requirements for Medicaid but cannot afford private insurance. Closing the coverage gap through Medicaid expansion would increase the number of insured individuals and expand access to health care for millions of people.

The varying definitions of “medical necessity” across states further impedes access, coverage, and affordability of care. While the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 was created to provide equal coverage and benefits for mental health and substance use services and for physical health, insurers have found ways to skirt parity rules, particularly during the pandemic.46 In 2020, California passed a law that requires insurers to expand medical necessity determinations to “generally accepted standards of mental health and substance use disorder care,” meaning they must evolve their definitions of necessity to reflect current standards of care.47 Both state and national policies must compel insurers to expand medical necessity determinations to enhance access and coverage. However, policies expanding medical necessity determinations must be enacted together with policies addressing network inadequacy. Focusing solely on medical necessity can only help so much if providers do not accept insurance.

Telehealth has garnered more national attention and has been used more than before the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the large increases in telehealth use, particularly for mental and behavioral health services, coverage for these services remains limited. While the U.S. House of Representatives has passed legislation to extend telehealth access, these policies need to become long-term changes. Expanding the use of technology that makes health care more convenient for patients, like telehealth, and ensuring that insurance companies cover care delivered through such technology over the long term, will allow many more people to access health care, as shown during the pandemic. However, providers will need to keep up with the increased demand, so policymakers’ efforts to expand the use of technology in health care should align with efforts to increase the number of mental health professionals.

Finally, policymakers should make a greater effort to enact policies that integrate mental and physical health. While many PCPs are stretched thin, these providers are often a patient’s first point of entry into the health care system. Our health care system must both implement models in which PCPs are more appropriately equipped to triage mental health issues and promote greater collaboration and coordination among primary care and mental health providers. The integrated behavioral health model requires training, costs, and changes to current systems, but it serves patients better. Furthermore, physicians favor the model.48

With a growing share of the population reporting mental health and substance use issues, policymakers need to prioritize expanding access, coverage, and affordability of care. In the near term, expanding Medicaid coverage across all states, enforcing parity laws that have an evolving definition of medical necessity across all insurers, expanding coverage of telehealth services, and integrating mental health care into the primary care setting will all provide immediate benefits to millions of Americans.

Notes

- The 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) classified adults with any mental illness as adults who had any mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder in the past year of sufficient duration to meet DSM-IV criteria.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, SAMHSA. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. Accessed Aug. 1, 2022.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-55). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, SAMHSA. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/. Accessed Aug. 1, 2022.

- Weinberger A, Gbedemah M, Martinez A, Nash D, Galea S, Goodwin, R. Trends in depression prevalence in the USA from 2005 to 2015: widening disparities in vulnerable groups. Psychol Med. 2018;48(8):1308-1315. doi:10.1017/S0033291717002781.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Survey: Data Summary and Trends Report, 2009-2019. CDC; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/mental-health/index.htm. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Panchal N, Rudowitz R, Cox C. Recent Trends in Mental Health and Substance Use Concerns Among Adolescents. Washington, DC: KFF; June 28, 2022. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/recent-trends-in-mental-health-and-substance-use-concerns-among-adolescents/. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP-AACAP-CHA declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/. Published Oct. 19, 2021. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Protecting Youth Mental Health. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2022.

- KFF. State Health Facts. Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) as of Sept. 30, 2021. San Francisco, CA: KFF. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/mental-health-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- Andrilla CHA, Patterson DG, Garberson LA, Coulthard C, Larson EH. Geographic variation in the supply of selected behavioral health providers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6):S199-S207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.004. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- Dobis EA, Krumel TP, Cromartie J, Conley K, Sanders A, Ortiz R. Rural America at a Glance. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; November 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/102576/eib-230.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- National Resident Matching Program. National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2022 Main Residency Match. NRMP; May 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/2022-Main-Match-Results-and-Data_Final.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA). https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Other-Insurance-Protections/mhpaea_factsheet. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- O’Connor K. Government steps up efforts to enforce parity law. Psychiatr News. 2022;57(3). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.pn.2022.03.3.32. Accessed July 11, 2022.

- Tolbert J, Orgera K, Damico A. What Does the CPS Tell Us About Health Insurance Coverage in 2020? San Francisco, CA: KFF; Sept. 23, 2021. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/what-does-the-cps-tell-us-about-health-insurance-coverage-in-2020/. Accessed April 21, 2022.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2019 (NSDUH-2019-DS0001). https://datafiles.samhsa.gov/. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Panchal N, Rae M, Saunders H, Cox C, Rudowitz R. How Does Use of Mental Health Care Vary by Demographics and Health Insurance Coverage? Washington, DC: KFF; March 24, 2022. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/how-does-use-of-mental-health-care-vary-by-demographics-and-health-insurance-coverage/. Accessed Aug. 9, 2022.

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Out-of-Network, Out-of-Pocket, Out-of-Options: The Unfulfilled Promise of Parity. Arlington, VA: NAMI; November 2016. https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/Out-of-Network-Out-of-Pocket-Out-of-Options-The/Mental_Health_Parity2016.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Pifer R. “Phantom” provider lists limit Medicaid mental healthcare access, study finds. Healthcare Dive. https://www.healthcaredive.com/news/phantom-provider-networkst-medicaid-mental-health-care-access-Health-affairs/626617/. Published July 6, 2022. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- Melek S, Davenport S, Gray TJ. Addiction and Mental Health vs. Physical Health: Widening Disparities in Network Use and Provider Reimbursement. Milliman Research Brief. November 2019. https://assets.milliman.com/ektron/Addiction_and_mental_health_vs_physical_health_Widening_disparities_in_network_use_and_provider_reimbursement.pdf. Accessed July 12, 2022.

- Pattani A. Patients seek mental health care from their doctor but find health plans standing in the way. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/article/primary-care-mental-health-insurance-barriers/. Published July 12, 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022.

- Guth M. State Policies Expanding Access to Behavioral Health Care in Medicaid. Washington, DC: KFF; Dec 9, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-policies-expanding-access-to-behavioral-health-care-in-medicaid/. Accessed Aug. 9, 2022.

- Charlesworth CJ, Zhu JM, Horvitz‐Lennon M, McConnell KJ. Use of behavioral health care in Medicaid managed care carve‐out versus carve‐in arrangements. Health Serv Res. 2021;56(5):805-816. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13703. Accessed Aug. 9, 2022.

- Bishop TF, Press MJ, Keyhani S, Pincus HA. Acceptance of insurance by psychiatrists and the implications for access to mental health care. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):176-181. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2862. Accessed July 6, 2022.

- Mark TL, Olesiuk W, Ali MM, Sherman LJ, Mutter R, Teich JL. Differential reimbursement of psychiatric services by psychiatrists and other medical providers. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;69(3):281-285. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700271.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Report to the Chairman, Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate: Mental Health Care, Access Challenges for Covered Consumers and Relevant Federal Efforts. Washington, DC: GAO; March 2022. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-104597.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicaid.gov. Behavioral health services. https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/benefits/behavioral-health-services/index.html. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Physician Acceptance of New Medicaid Patients: Findings From the National Electronic Health Records Survey. Washington, DC: MACPAC; June 2021. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Physician-Acceptance-of-New-Medicaid-Patients-Findings-from-the-National-Electronic-Health-Records-Survey.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- NAMI. A Long Road Ahead: Achieving True Parity in Mental Health and Substance Abuse Care. Arlington, VA: NAMI; April 2015. https://www.nami.org/Support-Education/Publications-Reports/Public-Policy-Reports/A-Long-Road-Ahead/2015-ALongRoadAhead. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Pollitz K, Rae M, Mengistu S. Claims Denials and Appeals in ACA Marketplace Plans in 2020. Washington, DC: KFF; July 5, 2022. https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/claims-denials-and-appeals-in-aca-marketplace-plans/. Accessed July 18, 2022.

- Jetty A, Petterson S, Westfall JM, Jabbarpour Y. Assessing primary care contributions to behavioral health: a cross-sectional study using medical expenditure panel survey. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021; 12. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501327211023871.

- McGregor B, Mack D, Wrenn G, Shim RS, Holden K, Satcher D. Improving service coordination and reducing mental health disparities through adoption of electronic health records. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(9):985-987. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201400095

- Madden JM, Lakoma MD, Rusinak D, Lu CY, Soumerai SB. (2016, April 14). Missing clinical and behavioral health data in a large electronic health record (EHR) system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(6):1143-1149. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocw021.

- Privett N, Guerrier S. Estimation of the time needed to deliver the 2020 USPSTF preventive care recommendations in primary care. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(1):145-149. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305967. Epub 2020 Nov 19. PMID: 33211585; PMCID: PMC7750618.

- Finnegan J. Number of Americans with a primary care provider declined 2% over a decade, new study shows. Fierce Healthcare. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/practices/moving-wrong-direction-fewer-americans-have-a-primary-care-provider-new-study-shows. Published Dec. 17, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Ramanuj P, Ferenchik E, Docherty M, Spaeth-Rublee B, Pincus HA. Evolving models of integrated behavioral health and primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-0985-4.

- Katon WJ, Lin EH, von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2611-2620. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1003955.

- Weiner S. A growing psychiatrist shortage and an enormous demand for mental health services. AAMCNews. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/growing-psychiatrist-shortage-enormous-demand-mental-health-services. Published Aug. 9, 2022. Accessed August 25, 2022.

- Lo J, Rae M, Amin K, Cox C, Panchal N, Miller BF. Telehealth Has Played an Outsized Role Meeting Mental Health Needs During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington, DC: KFF; March 22, 2022. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/telehealth-has-played-an-outsized-role-meeting-mental-health-needs-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/. Accessed July 20, 2022.

- Health Resources and Services Administration, telehealth.hhs.gov. Policy changes during COVID-19. https://telehealth.hhs.gov/providers/policy-changes-during-the-covid-19-public-health-emergency/. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Morse S. House passes bill extending telehealth waivers through 2024. Healthcare Finance. https://www.healthcarefinancenews.com/news/house-passes-bill-extending-telehealth-waivers-through-2024/. Published July 28, 2022. Accessed Aug. 20, 2022.

- The White House. Fact sheet: President Biden to announce strategy to address our national mental health crisis, as part of unity agenda in his first State of Union. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/03/01/fact-sheet-president-biden-to-announce-strategy-to-address-our-national-mental-health-crisis-as-part-of-unity-agenda-in-his-first-state-of-the-union. Published March 1, 2022. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Koons C, Tozzi J. As suicides rise, insurers find ways to deny mental health coverage. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-05-16/insurance-covers-mental-health-but-good-luck-using-it. Published May 16, 2019. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- KFF. State Health Facts: Status of State Action on the Medicaid Expansion Decision, September 20, 2022. Washington, DC: KFF. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/. Accessed Aug. 7, 2022.

- Garfield R, Orgera K, Damico A. The Coverage Gap: Uninsured Poor Adults in States That Do Not Expand Medicaid. Washington, DC: KFF; Jan. 21, 2021. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/. Accessed Aug. 12, 2022.

- Huetteman E. Mental health services wane as insurers appear to skirt parity rules during pandemic. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/article/gao-report-mental-health-services-wane-as-insurers-appear-to-skirt-parity-rules-during-pandemic/. Published April 30, 2021. Accessed Aug. 9, 2022.

- Lara R. Enactment of Senate Bill 855 – Submission of Health Insurance Policies for Compliance Review [notice to health insurers]. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Insurance. Published Dec.10, 2020. http://www.insurance.ca.gov/0250-insurers/0300-insurers/0200-bulletins/bulletin-notices-commiss-opinion/upload/Notice-to-Health-Insurers-re-Requirements-of-Senate-Bill-855.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2022.

- Miller-Matero LR, Dykuis KE, Albujoq K, et al. Benefits of integrated behavioral health services: the physician perspective. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34(1):51-5. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000182. PMID: 26963777.