Although 1 in 5 adults in the United States had a mental illness in 2020, over half of those affected did not receive treatment1 because of barriers to accessing care.2 One significant barrier is the shortage of psychiatrists across the country.3 While research and policy tend to focus on psychiatrists and psychologists,4 other mental health professionals (e.g., social workers, counselors, and marriage and family therapists) represent a large share of the behavioral health workforce and provide a significant amount of behavioral health care.5 The training and expertise of each of these groups of mental health professionals also varies, which is important for health care providers and consumers to understand.

This snapshot summarizes the qualifications, educational requirements, and distribution of some of the main groups of independently licensed mental health providers across the country. While training and recruiting more doctors specializing in psychiatry is necessary, physicians will not alone be able to meet the needs of the more than 57 million people in the United States living with mental illness.6

Different Positions

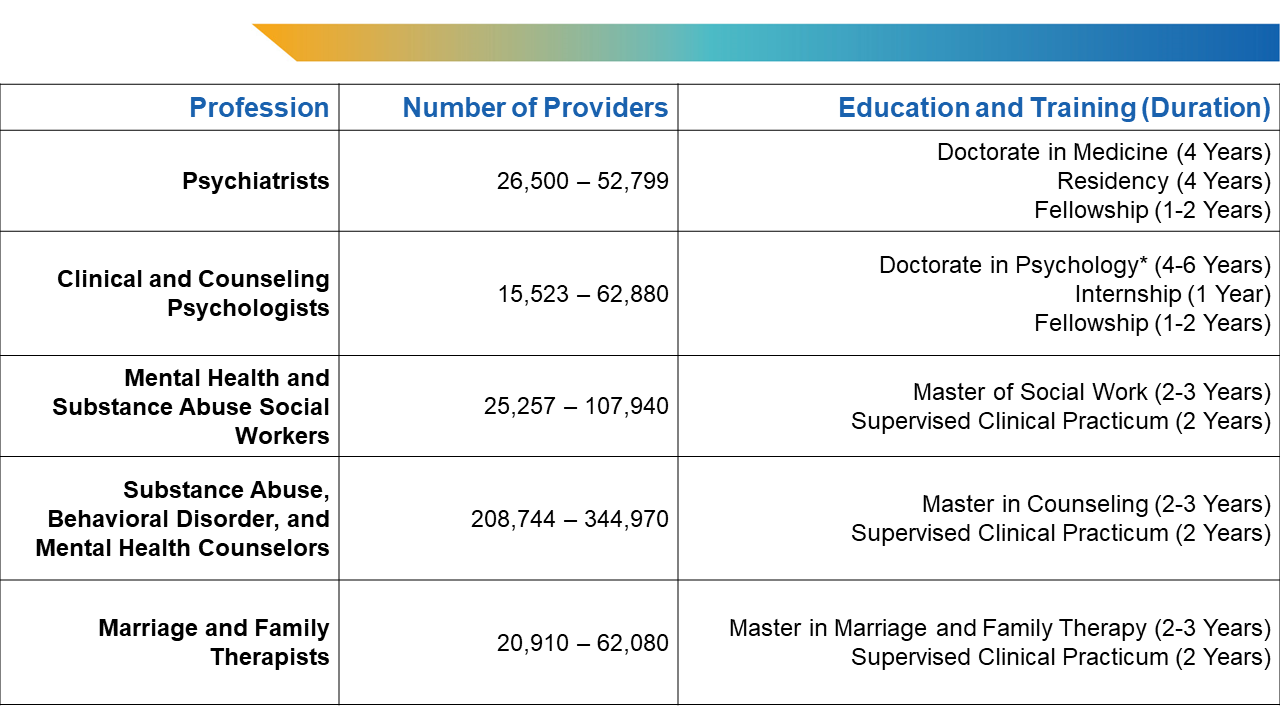

The behavioral health workforce typically includes psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, counselors, marriage and family therapists, and others — depending on the health care model and organization. Table 1 outlines the number of providers in each profession in the United States and their duration of education and training. These providers may specialize and receive their licenses or certificates from professional and state boards.7 The length of education and training remains the longest for psychiatrists (eight to 10 years), followed by psychologists (five to 10 years). Psychiatrists, unlike social workers, counselors, or marriage and family therapists, may prescribe medications to patients.8 Currently, five states allow psychologists to obtain certification to prescribe medication.9 Psychiatrists also typically see patients for shorter visits, and 53% no longer deliver psychotherapy.10,11,12 Although increasing the number of psychiatrists and psychologists is important, collaboration and promotion of task shifting13 may help better distribute providers to match need.

Table 1: Prevalence, Education, and Training of Mental Health Professionals in the United States.

*Certain state requirements allow individuals to practice after receiving their licensure and completing a master in psychology. Providers with a doctorate of philosophy in clinical or counseling disciplines are also qualified.

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. May 2022 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates; American Board of Medical Specialties. Board Certification Report 2021-2022; United States Census Bureau. 2021 American Community Survey Data.

Notably, Table 1 does not reflect all potential degrees and titles. For example, there are entry-level and assistant positions for social workers and counselors with an undergraduate education, but only behavioral health graduate degrees are displayed in Table 1. Despite opportunities for mental health certification and training, only 6.5% of nurse practitioners (NPs)14 and 2.0% of physician associates (PAs)15 reported a primary certification or specialized training in psychiatry or mental health. Primary care providers (PCPs) also frequently represent a first entry point for patients into the mental health care system. Adults with a major depressive episode were more likely to talk about their feelings with a general practitioner or family doctor (50.4%) than with a psychiatrist (39.4%) in 2021.2,6 These numbers underscore the need for increased behavioral health access and integration in primary care settings. While PCPs may receive behavioral health training during residency,16 few choose to complete additional specializations17 — only 1,833 physicians are certified in addiction medicine.18 Finally, nonlicensed professionals such as community health workers and peer networks also extend important types of support.19,20

Overview of Shortages

Nationally, projections have revealed an estimated shortage of between 14,280 and 31,081 psychiatrists by 2024.21 Over half (51%) of counties in the United States lack practicing psychiatrists.22 The number of psychiatry residency applicants has also declined over the past two years.23 Alarmingly, factors such as burnout,24 retirement,25 and lower rates of reimbursement, which dissuades providers from accepting insurance,26 may lead to a 20% decrease in the number of adult psychiatrists by 2030.27

However, substantial growth across other behavioral health disciplines is expected, including a 114% increase in the supply of social workers and a 37% increase in the supply of marriage and family therapists.27 Recent proposals also suggest that expanding the roles of PAs and psychiatric advanced practice nurses (APRNs) may reduce behavioral health workforce shortages, especially in rural communities that lack specialized clinicians.2,28 Many PAs and APRNs have prescriptive authority, but that depends on state scope-of-practice laws.29,30

Significant variation exists in the quantity of providers per capita across the United States. In 2022, the national average was approximately eight psychiatrists per 100,000 population. Broadly, the number of psychiatrists per 100,000 population ranges from two in Mississippi and Louisiana to 40 in the District of Columbia. Generally, areas with fewer psychiatrists have more social workers as well as substance abuse, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors, which highlights opportunities to bridge these shortages.

Going Forward

Altogether, the highlighted trends emphasize the importance of innovation in service delivery, collaborative models, expansion of behavioral health into primary care settings, and recruitment and retention of psychiatrists. Integrated practices using teams of psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, primary care providers, patient navigators, and case managers are becoming increasingly necessary to expand accessibility of mental health services.31 Public health approaches tailored to specific populations and prevention efforts may reduce the rate of mental health conditions, along with limiting the growth in demand for providers and services.32 Future policy reform must include evaluating and appropriately leveraging the various roles of each provider type, consider how best to deliver care across a wide range of populations and communities, and promote consumer health literacy and transparency in services and professional competencies.

Notes

- Mental Health America. The State of Mental Health in America — 2023 Key Findings. https://mhanational.org/issues/state-mental-health-america. Accessed Aug. 1, 2023.

- Modi H, Orgera K, Grover A. Exploring Barriers to Mental Health Care in the U.S. Washington, DC: AAMC. https://www.aamcresearchinstitute.org/our-work/issue-brief/exploring-barriers-mental-health-care-us. Published Oct. 10, 2022. Accessed July 24, 2022.

- Weiner S. A growing psychiatrist shortage and an enormous demand for mental health services. AAMCNews. https://www.aamc.org/news/growing-psychiatrist-shortage-enormous-demand-mental-health-services. Published Aug. 9, 2022. Accessed July 11, 2023.

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Health workforce shortage areas. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas. Accessed July 31, 2022.

- Counts N. Understanding the U.S. Behavioral Health Workforce Shortage. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/explainer/2023/may/understanding-us-behavioral-health-workforce-shortage. Published May 18, 2023. Accessed June 13, 2023.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, SAMHSA. https://www.samhsa.gov/data. Accessed June 22, 2023.

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Credentialing, Licensing, and Education. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/credentialing-licensing-and-education. Published May 7, 2018. Accessed June 5, 2023.

- Zhang P, Patel P. Practitioner and Prescriptive Authority. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574557. Published Sept. 27, 2021. Accessed July 5, 2023.

- American Psychological Association Services. RxP: A Chronology. https://www.apaservices.org/practice/advocacy/authority/prescription-chronology. Published Jan. 8, 2014. Accessed Aug. 31, 2023.

- American Psychological Association. How Long Will It Take for Treatment to Work? PTSD Clinical Practice Guideline. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/patients-and-families/length-treatment. Accessed July 14, 2023.

- Tandmon D, Olfson M. Trends in outpatient psychotherapy provision by U.S. Psychiatrists: 1996-2016. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2)110-121. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21040338. Published Dec. 8, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- Cruz M, Roter DL, Cruz RF, Wieland M, Larson S, Cooper LA, Pincus HA. Appointment length, psychiatrists' communication behaviors, and medication management appointment adherence. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):886-892. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201200416. Accessed July 17, 2023.

- Grant KL, Simmons MB, Davey CG. Three nontraditional approaches to improving the capacity, accessibility, and quality of mental health services: an overview. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(5):508-516. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700292. Accessed July 19, 2023.

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. NP Facts. https://storage.aanp.org/www/documents/NPFacts__111022.pdf?_gl=1*11knbz5*_gcl_au*NzczMjYzNjU1LjE2ODg3NDQ5NTI. Published Nov. 1, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Statistical Profile of Certified PAs. https://www.nccpa.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2021StatProfileofCertifiedPAs-A-3.2.pdf. Published Aug. 1, 2022. Accessed June 6, 2023.

- Bech A, Page C, Buche J, Schoebel V, Wayment C. Behavioral Health Service Provision by Primary Care Physicians. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan School of Public Health Behavioral Health Workforce Research Center. https://www.behavioralhealthworkforce.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Y4-P10-BH-Capacityof-PC-Phys_Full.pdf. Published Oct. 1, 2019. Accessed July 12, 2023.

- American Board of Family Medicine. Additional Certifications Available to Family Medicine Physicians. https://www.theabfm.org/added-qualifications/additional-certifications-available-family-physicians. Accessed July 17, 2023.

- Scutti S. 21 million Americans suffer from addiction. Just 3,000 physicians are specially trained to treat them. AAMCNews. https://www.aamc.org/news/21-million-americans-suffer-addiction-just-3000-physicians-are-specially-trained-treat-them. Published Dec. 18, 2019. Accessed July 6, 2023.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). On the Front Lines of Health Equity: Community Health Workers. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/community-health-worker.pdf. Published April 5, 2021. Accessed June 13, 2023.

- Shalaby RAH, Agyapong VIO. Peer support in mental health: literature review. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(6):e15572. doi:10.2196/15572. Accessed June 9, 2023.

- Satiani A, Niedermier J, Satiani B, Svendsen DP. Projected workforce of psychiatrists in the United States: a population analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(6):710-713. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201700344. Accessed June 28, 2023.

- Andrilla CHA, Patterson DG, Garberson LA, Coulthard C, Larson EH. Geographic variation in the supply of selected behavioral health providers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6):S199-S207. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.01.004. Accessed Oct. 5, 2023.

- AAMC. ERAS Statistics. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/eras-statistics-data. Accessed July 26, 2023.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Addressing Health Worker Burnout: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory on Building a Thriving Health Workforce. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/priorities/health-worker-burnout/index.html. Published May 9, 2022. Accessed June 27, 2023.

- AAMC. Physician Specialty Data Report: Active Physicians by Age and Specialty, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/active-physicians-age-and-specialty-2019. Accessed July 19, 2023.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. State Strategies to Recruit and Retain the Behavioral Health Workforce. https://www.ncsl.org/health/state-strategies-to-recruit-and-retain-the-behavioral-health-workforce. Published May 20, 2022. Accessed July 22, 2022.

- HRSA Health Workforce. Behavioral Health Workforce Projections, 2017-2030. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/data-research/projecting-health-workforce-supply-demand/behavioral-health. Accessed June 8, 2023.

- Talley RM. Addressing psychiatric workforce shortages: the role of advanced practice psychiatric nurses and physician assistants. Psychiatr Serv. 2023;74(7):770. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.20220599. Accessed Aug. 1, 2023.

- American Medical Association. Physician Assistant Scope of Practice. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/arc-public/state-law-physician-assistant-scope-practice.pdf. Accessed Sept. 22, 2023.

- American Medical Association. State Law Chart: Nurse Practitioner Prescriptive Authority. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/specialty%20group/arc/ama-chart-np-prescriptive-authority.pdf. Accessed Sept. 21, 2023.

- American Psychiatric Association Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine. Dissemination of Integrated Care Within Adult Primary Care Settings: The Collaborative Care Model. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Professional-Topics/Integrated-Care/APA-APM-Dissemination-Integrated-Care-Report.pdf. Published March 7, 2016. Accessed July 26, 2023.

- Fusar-Poli P, Correll CU, Arango C, Berk M, Patel V, Ioannidis JPA. Preventive psychiatry: a blueprint for improving the mental health of young people. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):200-221. doi:10.1002/wps.20869. Accessed Sept. 21, 2023.