Not-for-profit hospitals are often evaluated by researchers and policymakers for the benefits they provide to patients and communities. Benefits, for tax-reporting purposes, are broadly outlined by regulation to include underreimbursed costs or costs that haven’t been reimbursed for patient care, research, education, and other investments for improving community health.1 While well-intentioned in advocating for patients, researchers and some policymakers have omitted from their examinations important and heavily relied-upon health care services by narrowly defining community benefit as charity care; specifically, free or discounted services for patients in need of financial assistance.2 Not surprisingly, given the increase in insurance coverage following the enactment of the Affordable Care Act, the total amount of charity care provided by hospitals using this narrow definition has decreased over time, particularly in states that have expanded Medicaid coverage.3

While the costs of charity care are important components of the benefits provided to communities, they do not capture the full range of services provided by hospitals and health systems, which meet the IRS’ broader definition4 of community benefit; the costs of clinical care beyond charity care provided to communities are particularly substantial, but little of them is understood by policymakers and the general public.

Academic health systems (AHSs) are also pivotal in addressing care gaps within their communities by providing a full spectrum of clinical care to patients, often providing less common or highly complex services across states or regions.5 Teaching hospitals in these systems have been found to be in the top quartile of spending on community benefits.6 AHSs spend billions of dollars each year ensuring necessary care is available in times of crisis, most obviously through essential and acute standby services, such as Level I trauma centers and verified burn centers.7 Studies have shown that mortality rates are much lower when care is provided at trauma centers, compared to hospitals that do not have such services, further illustrating their benefit.8

The AAMC Research and Action Institute used the 2022 American Hospital Association Annual Survey Database for this data snapshot to highlight the discrepancies in services offered across short-term general and critical-access hospitals and how these discrepancies relate to charity care, and the policy implications of defining and interpreting charity care differently across institutions.

Nearly 1,700 specialty hospitals, including 1,012 for-profit and 680 non-profit, were excluded from the analysis to better understand the range of services provided by short-term general hospitals and thus our results may understate the full effect. Across all for-profit hospitals, including specialty hospitals, less than half offer general medical and surgical services (data not shown). The remainder of the analyses include only the short-term general, non-specialty hospitals; and even among those, the for-profit hospitals are less likely to offer many services compared to not-for-profit and teaching short-term general hospitals.

Not-for-profit teaching hospitals offer more distinct types of services than for-profit and nonteaching hospitals. While essential services are often sought after and needed during crises, these services are mostly found in teaching hospitals, especially those with not-for-profit status. Not-for-profit teaching hospitals that offer these essential services carry the burden of cost to run the programs, many of which are less profitable and not factored into the calculation of charity care.9 For instance, Level I trauma centers must be fully staffed at all times in anticipation of community need, but they are unlikely to be at patient capacity on any given day.10 11 While there is a cost to having these services on standby, it is a clear community benefit, even if it might not be defined as such.

Past research that analyzed the profitability of services defined which services were “profitable” and “unprofitable.”12 Services categorized as profitable include orthopedic services, sports medicine, and various surgeries (e.g., general, neurosurgery, vascular, and outpatient), while the less profitable or unprofitable services tend to be emergent services (e.g., trauma centers), those provided at burn centers, psychiatric services, and substance use disorder care.13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Literature examining birthing rooms and transplant services show mixed profitability statuses.20 21 22

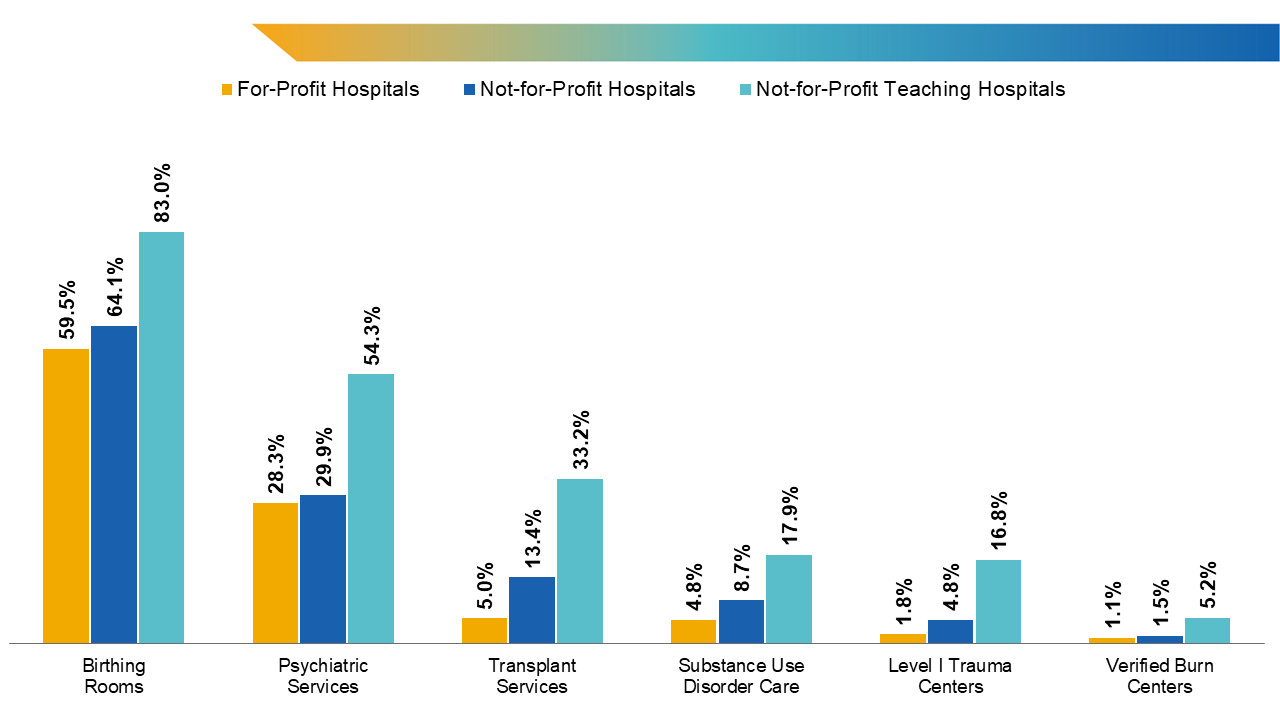

Across ownership types, not-for-profit hospitals were more likely than for-profit hospitals to offer clinical services, including those that were more likely to be unprofitable, such as trauma centers and psychiatric services (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Share of general, acute care hospitals offering services by ownership type. Note: Hospitals designated as “church”; “state government”; and other, not-for-profit ownership types were classified as not-for-profit institutions. Transplant services include bone marrow, heart, kidney, liver, lung, tissue, and/or other transplants.

Source: American Hospital Association Annual Survey Database for fiscal year 2022.

Though teaching hospitals (both for-profit and not-for-profit) account for only 28.1% of total hospitals examined, they represent the majority of beds and discharges (62.1% and 66.5%, respectively). Lengths of stay and the numbers of hospital beds and discharges are additional benchmarks to indicate costs and capacities of hospitals, as increased lengths of stay incur higher costs.

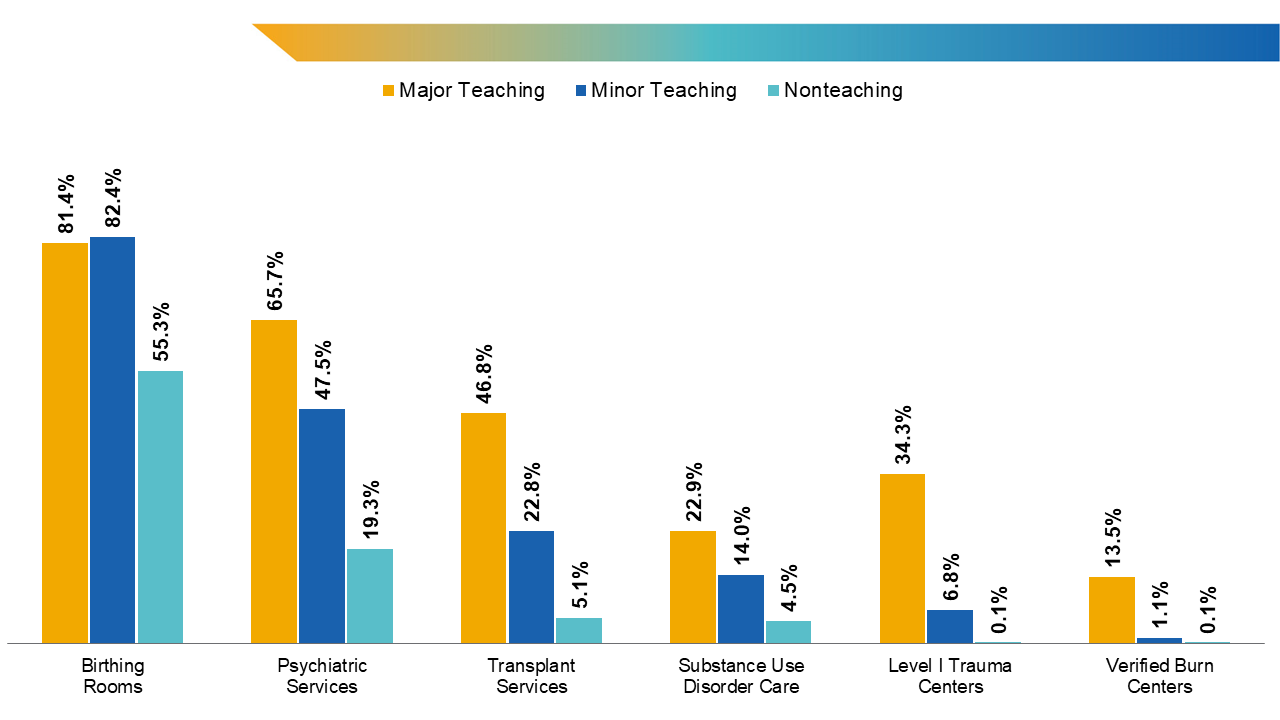

Teaching hospitals also are more likely to offer more services: At any given teaching hospital, on average, 45.8% of the 32 examined clinical services23 are available; nonteaching hospitals offer only 24.3% of these same services. Like not-for-profit hospitals, major teaching hospitals (i.e., those with resident-to-bed ratios greater than or equal to 25.0%) are most likely to offer complex services, including the less profitable ones like substance use disorder care and trauma and burn centers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Share of general, acute care hospitals offering services by teaching status. Note: Major teaching hospitals were classified as having resident-to-bed ratios equal to or greater than 25%. Transplant services include bone marrow, heart, kidney, liver, lung, tissue, and/or other transplants.

Source: American Hospital Association Annual Survey Database for fiscal year 2022.

Looking more closely at major teaching hospitals, which make up 30.7% of all teaching hospitals, there are additional discrepancies in service provision; for example, 65.7% of major teaching hospitals and 73.2% of AAMC-member health systems and hospitals offer psychiatric services, compared to just 19.3% of nonteaching hospitals. Major teaching hospitals also significantly outpace nonteaching hospitals in the breadth and numbers of services offered, with not-for-profit, major teaching hospitals taking the lead, offering an average of 19 different services out of the service types examined, while nonteaching hospitals only offer an average of eight services.

Ultimately, patients and communities rely on AHSs and not-for-profit hospital systems for wide ranges of benefits beyond charity care. Alongside AHS workforce-capacity building and research efforts, provision of standby services (e.g., trauma care and burn centers) emulates the community-benefit standard, as defined by the IRS. Moreover, studies show that the amount of charity care provided does not directly correlate with overall community benefit, as some hospitals may provide a great deal of charity care, but the overall community benefit is low.24

While there has been a steady improvement in systemic efficiency, changing criteria for tax-exempt status based on lower charity-care provision will result in many health systems (including AHSs) having to make trade-offs and likely lessening or eliminating already scarce clinical services, which hold significant value to patients for their unique qualities and because the teaching hospital status has been found to be associated with lower mortality rates for common conditions.25 From the patient perspective, access to these services can mean the difference between life and death, particularly in critical situations (e.g., accidents, firearm injuries, and fires) that require specialized care. Economists and policymakers must carefully assess the roles of federal subsidies and tailored payments to AHSs and not-for-profit hospitals to help ensure continued access to essential clinical care in nonteaching and for-profit hospitals.

Methods

These analyses used a comprehensive, national hospital dataset from the American Hospital Association Annual Survey Database for fiscal year (FY) 2022, which included hospital ownership types and services offered. Hospitals that provide any of the 32 examined clinical services were identified.17 Hospitals included in the analyses are short-term, nonfederal hospitals that provide general medical and surgical care, and critical-access hospitals located in the 50 states and Washington, D.C. Also included are nonspecialty hospitals that reported not offering general medical and surgical care (typically, critical-access hospitals). Hospitals with “church”; “state government”; and other, not-for-profit ownership types were classified as not-for-profit organizations.

Hospital service information from the database was supplemented with trauma center data from the American College of Surgeons’ list of hospitals and facilities26 and verified data on burn centers from the American Burn Association.27

According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ FY 2024 Inpatient Prospective Payment System Correction Notice to the Final Rule impact file28 and the reported number of full-time-equivalent residents in the FY 2022 American Hospital Association annual survey, teaching hospitals are defined as having intern- and resident-to-bed ratios greater than 0. Hospitals with resident-to-bed ratios greater than 0 were classified as teaching hospitals, and the hospitals with ratios equal to or above 0.25 were classified as major teaching hospitals.

A hospital share offering a service was computed as the number of hospitals in a category offering the service divided by all responding hospitals in the category. Categories include major teaching hospitals, minor teaching hospitals, nonteaching hospitals, all teaching hospitals, not-for-profit hospitals, for-profit hospitals, and not-for-profit teaching hospitals.

- Zare H, Eisenberg M, Anderson G. Charity care and community benefit in non-profit hospitals: definition and requirements. Inquiry. 2021;58:469580211028180. doi:10.1177/00469580211028180 Back to text ↑

- IRS. 2023 Instructions for Schedule H (Form 990). Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/i990sh.pdf Back to text ↑

- Dranove D, Garthwaite C, Ody C. Uncompensated care decreased at hospitals in Medicaid expansion states but not at hospitals in nonexpansion states. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(8):1471-1479. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1344 Back to text ↑

- IRS. Charitable hospitals - general requirements for tax-exemption under section 501(c)(3). Updated July 1, 2024. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits/charitable-hospitals-general-requirements-for-tax-exemption-under-section-501c3 Back to text ↑

- Fisher K. Academic health centers save millions of lives. AAMCNews. Published June 4, 2019. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/news/academic-health-centers-save-millions-lives Back to text ↑

- Alberti PM, Sutton KM, Baker M. Changes in teaching hospitals’ community benefit spending after implementation of the Affordable Care Act. Acad Med. 2018;93(10):1524-1530. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002293 Back to text ↑

- Fisher K. Academic health centers save millions of lives. AAMCNews. Published June 4, 2019. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/news/academic-health-centers-save-millions-lives Back to text ↑

- MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, et al. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):366-378. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa052049 Back to text ↑

- Horwitz JR, Nichols A. Hospital service offerings still differ substantially by ownership type. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(3):331-340. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01115 Back to text ↑

- MacKenzie EJ, Hoyt DB, Sacra JC, et al. National inventory of hospital trauma centers. JAMA. 2003;289(12):1515-1522. doi:10.1001/jama.289.12.1515 Back to text ↑

- Faul M, Sasser SM, Lairet J, Mould-Millman NK, Sugerman D. Trauma center staffing, infrastructure, and patient characteristics that influence trauma center need. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(1):98-106. doi:10.5811/westjem.2014.10.22837 Back to text ↑

- Horwitz JR. Making profits and providing care: comparing nonprofit, for-profit, and government hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(3):790-801. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.790 Back to text ↑

- Horwitz JR, Nichols A. Hospital service offerings still differ substantially by ownership type. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(3):331-340. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01115 Back to text ↑

- Horwitz JR. Making profits and providing care: comparing nonprofit, for-profit, and government hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(3):790-801. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.790 Back to text ↑

- Eskoz R, Peddecord KM. The relationship of hospital ownership and service composition to hospital charges. Health Care Financ Rev. 1985;6(3):51-58. Back to text ↑

- Wilson M, Cutler D. Emergency department profits are likely to continue as the affordable care act expands coverage. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):792-799. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0754 Back to text ↑

- Lindrooth RC, Konetzka RT, Navathe AS, Zhu J, Chen W, Volpp K. The impact of profitability of hospital admissions on mortality. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(2 Pt 2):792-809. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12026 Back to text ↑

- Cerullo M, Yang KK, Roberts J, McDevitt RC, Offodile AC II. Private equity acquisition and responsiveness to service-line profitability at short-term acute care hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(11):1697-1705. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00541 Back to text ↑

- Corpron CA, Martin AE, Roberts G, Besner GE. The pediatric burn unit: a profit center. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(6):961-963. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.02.033. Accessed from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15185234/, July 1, 2024. Back to text ↑

- Horwitz JR, Nichols A. Hospital service offerings still differ substantially by ownership type. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(3):331-340. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01115 Back to text ↑

- Horwitz JR. Making profits and providing care: comparing nonprofit, for-profit, and government hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(3):790-801. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.790 Back to text ↑

- Cerullo M, Yang KK, Roberts J, McDevitt RC, Offodile AC II. Private equity acquisition and responsiveness to service-line profitability at short-term acute care hospitals. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(11):1697-1705. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00541 Back to text ↑

- The 32 identified services include: acute, long-term care; HIV and AIDS services; birthing rooms/labor, delivery, and recovery rooms/labor, delivery, recovering, and postpartum rooms; bone marrow transplants; cardiac intensive care; case management; chemotherapy; crisis prevention; computerized tomography; electrodiagnostic services; an emergency department; a fertility clinic; general medical and surgical care; geriatric services; heart transplants; kidney transplants; Level I trauma centers; liver transplants; lung transplants; MRI; neonatal intensive care; neurological services; obstetrics care; oncology services; orthopedic services; other transplants; psychiatric care; substance use disorder care; tissue transplants; ultrasound; verified burn centers; and women’s health centers or services. Back to text ↑

- Zare H, Eisenberg M, Anderson G. Charity care and community benefit in non-profit hospitals: definition and requirements. Inquiry. 2021;58:469580211028180. doi:10.1177/00469580211028180 Back to text ↑

- Dashoff J. JAMA study finds lower mortality rates at U.S. teaching hospitals. AAMCNews. Published May 23, 2017. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/news/jama-study-finds-lower-mortality-rates-us-teaching-hospitals Back to text ↑

- American College of Surgeons. Hospital and facilities. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://www.facs.org/hospital-and-facilities/ Back to text ↑

- American Burn Association. Verified burn centers. Accessed August 19, 2024. https://members.ameriburn.org/verified-burn-centers Back to text ↑

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. FY 2024 IPPS final rule home page. Updated March 5, 2024. Accessed August 22, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/prospective-payment-systems/acute-inpatient-pps/fy-2024-ipps-final-rule-home-page Back to text ↑