Most health care workforce analyses in the past 20 years have projected a shortage of physicians and other health care professionals, and these shortages have only worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic. Within medicine, significant attention has been paid to the shortage of primary care doctors, though shortages across most specialties and subspecialties are even more striking.

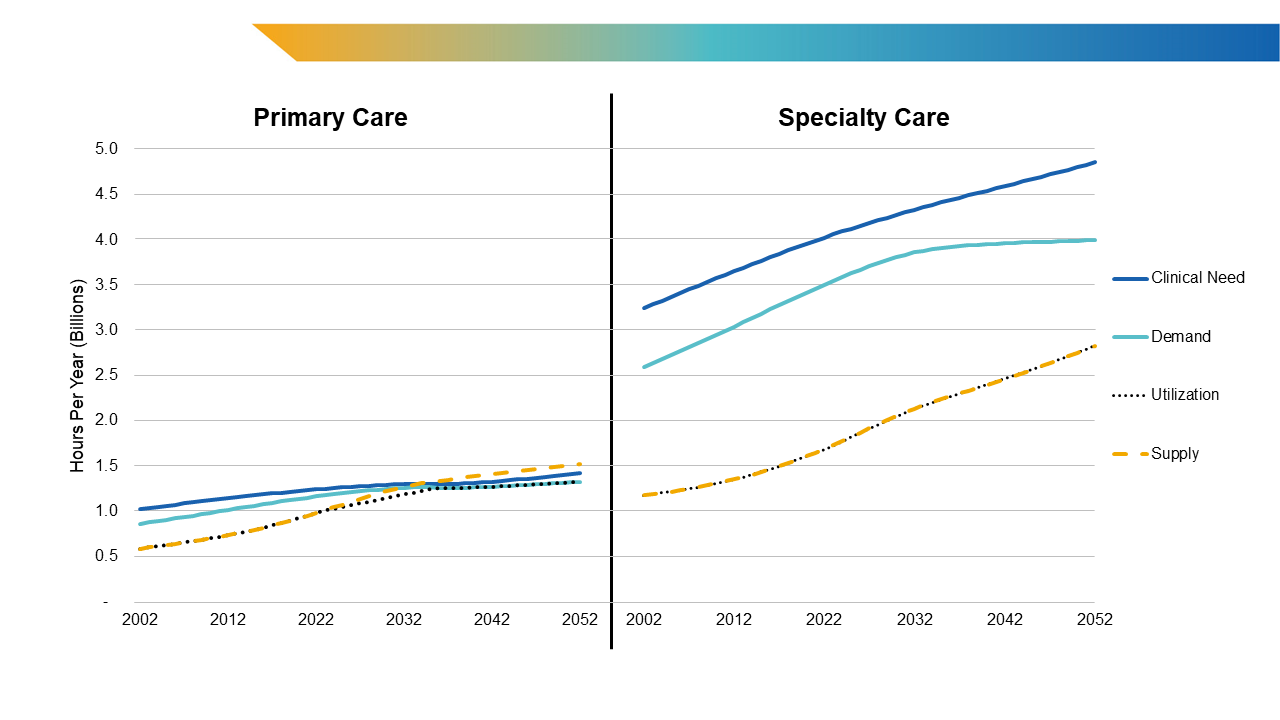

Federal health care workforce projections models continue to highlight potential shortages of primary care physicians while simultaneously projecting a surplus of other advanced practice clinicians (APCs) in primary care. For instance, the Health Resources and Services Administration’s (HRSA’s) Bureau of Health Workforce estimates that the United States is facing a current shortage of 43,130 primary care physicians and expects that shortage to increase by an additional 24,890 primary care physicians (including 11,380 internists, 3,100 pediatricians, 1,590 geriatricians, and 8,820 family medicine doctors) by 2036. In other words, HRSA projects a total shortage of 68,020 primary care physicians by 2036. However, HRSA also estimates a surplus of 74,770 nurse practitioners (NPs) and 13,190 physician associates (PAs) in primary care during the same time period (Figure 1).

Figure 1. HRSA’s Primary Care Provider Shortage Estimates and Projections, 2021-2036

Source: National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Health Workforce Projections Dashboard. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/workforce-projections

How can a shortage of primary care physicians and a surplus of other primary care providers exist side by side?

In actuality, they are not likely to. Indeed, the primary care shortage may be effectively alleviated given such a surplus of nonphysician providers. NPs and PAs are not limited by the specialty of their initial training and can more readily fill market voids compared with physicians whose training is more extensive and standardized in an area of specialization. In other words, primary care physicians primarily practice primary care, while NPs and PAs can and do frequently work in other settings and specialties in addition to their critical roles in primary care.

Physician workforce projections models have too often failed to account for how the roles of other clinicians are changing; realistic models must account for changing practice patterns among physicians and nonphysicians. The institute previously noted the expanding roles and contributions of NPs and PAs and the need to incorporate knowledge and data on the complexities of team-based care workloads into projections models.

An Innovation in Workforce Modeling Is Forthcoming

The AAMC (Association of American Medical Colleges), in collaboration with RAND, has developed an innovative physician workforce projections model using system dynamics methods that allows users to model changes in clinical care provision and the health of populations, where such data are available. This will eventually allow for more rapid and insightful projections that take into account shifts in both provider and patient populations and behaviors.

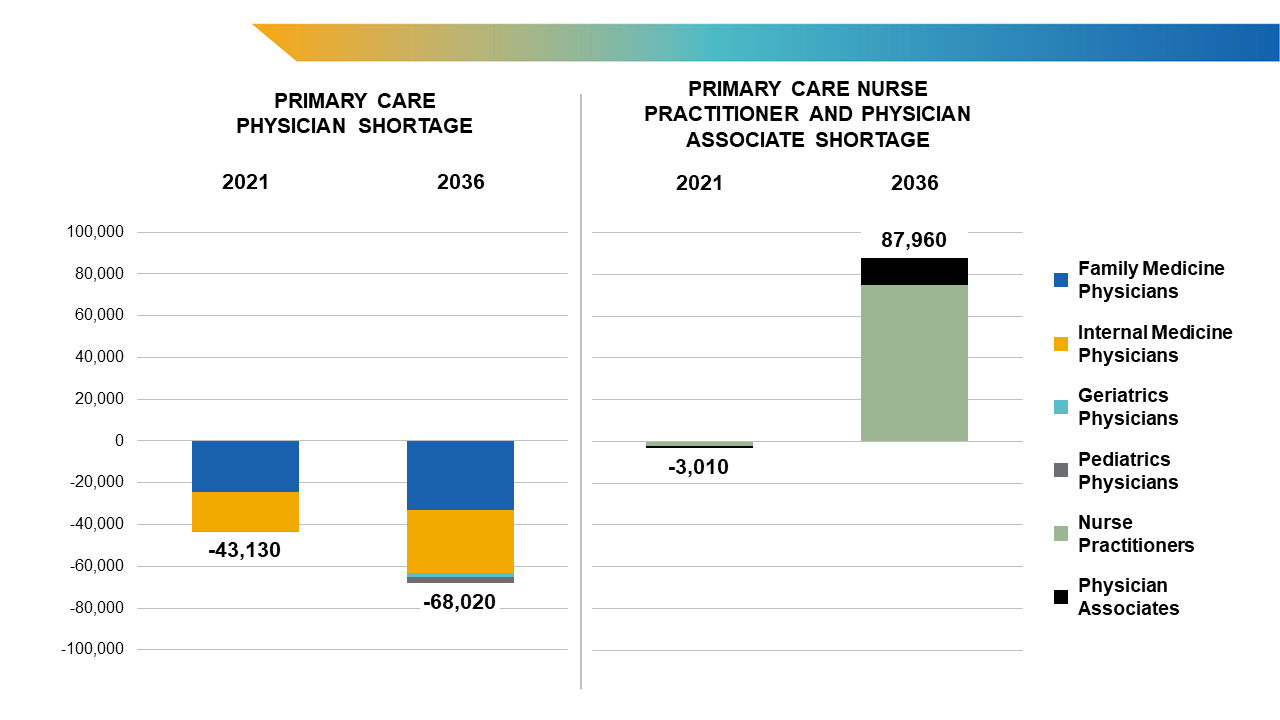

Preliminary findings from this new model, which the AAMC presented at its annual meeting this month, suggest that task shifting may greatly decrease the shortage of primary care physicians but have less of an impact on other specialties. As will be discussed in a full report to be published in early 2025, early data projections show that the rapidly increasing supply of NPs and PAs can meet the demand for providing primary care to the U.S. population within the next decade (Figure 2). In fact, policies to accelerate the provision of care by nonphysician providers, when appropriate, may be able to alleviate shortages in primary care at the national level within the next five years (figure not shown).

For nonprimary care physician specialties, the outlook is less optimistic. The model projects that the nonprimary care physician specialty workforce will experience shortages for the next three decades at least (Figure 2). This is the case even with the accelerated provision of care by nonphysicians (figure not shown). Current assumptions in the model show that while the overall shortage of physicians is likely to persist for at least the next few decades, in the long term, those shortages will not be in primary care.

Projections Can Inform Policy, But More Action Is Needed

The delivery of primary care services remains essential to a well-functioning health system, and many of these services can and will be provided by nonphysicians. Research already suggests that nonphysicians are increasingly delivering care to patients in ambulatory and other settings.1 Within primary care, this most commonly includes treating less complex conditions (e.g., urinary tract infections, low back pain, acute respiratory infections) in patients with fewer comorbidities. Additionally, in many specialties and subspecialties, nonphysician APCs also complement physician work. This task shifting has helped increase capacity, allowing oncologists, surgeons, and other specialists to see more patients.

Given the ability to shift the work of primary care from physicians to APCs, it is possible to eliminate primary care shortages in the next decade, but only if that workforce is efficiently and effectively located and utilized. This requires that health professionals and health systems be able to actively triage patients to the right care providers at the right time, regardless of how or why those patients are seeking care. Due to the lack of a cohesive national system to facilitate this triage and the current inability of even large, geographically dispersed health systems to efficiently assign patients to providers, this is still unlikely.

Absent major changes at the state, local, and federal levels, such a major shift in how care is delivered is likely to happen at a slower pace than necessary. Fully utilizing PAs and NPs, as well as social workers, pharmacists, and other professionals, to care for patients with acute and chronic problems is still unlikely to eliminate clinical shortages for the foreseeable future. If current trends continue, more physicians and APCs may need to be trained in other specialties and subspecialties to treat the increasing burden of short- and long-term disease experienced by a growing, aging population. The nation will not satisfy the need, demand, or ideal utilization of primary care and subspecialty services without both increased production of clinicians and major shifts in clinical practice.

As data collection improves and researchers better understand how care being delivered by different health professionals is occurring (in colocated teams or separately) and changing, the new RAND-AAMC system dynamics model will be able to incorporate that information and alter projections accordingly. This model will be publicly usable in the future and will allow health professions educators and policymakers to learn from various scenarios and subsequently alter their strategies effectively to ensure the health care system meets our future needs.

More detailed scenarios from the new RAND-AAMC workforce model will be published by the AAMC Workforce Studies team in the coming months. To receive periodic updates on the development of this model and its projections, visit rand.org/health-care/projects/physician-workforce-projections/sign-up.

- Patel SY, Auerbach D, Huskamp HA, et al. Provision of evaluation and management visits by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the USA from 2013 to 2019: cross-sectional time series study. BMJ. 2023;382:e073933. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-073933 Back to text ↑